I am happy.

It feels weird to say that on this blog, and also slightly wrong. Like I shouldn’t be.

When my son was diagnosed with a life-limiting condition back in July 2015, I was thrown into a maelstrom of emotions. Most of all, I couldn’t imagine ever laughing again, let alone feeling the deep contentment that I’ve settled into lately. But I guess that’s the thing about emotions – they don’t hang around forever.

Now, I have so much to be happy about: I have a lovely house and garden; strong family support around me; T is growing into an interesting and studious young man who frequently makes me laugh out loud with his quirky take on life; I’ve been able to get into more acting again; meditation has changed my outlook quite a lot; and going on HRT has also made a huge difference in eliminating some of the anxiety that I’d come to think of as normal for me. After two years of writing a gratitude diary every night I certainly don’t struggle to find three things to put down each day.

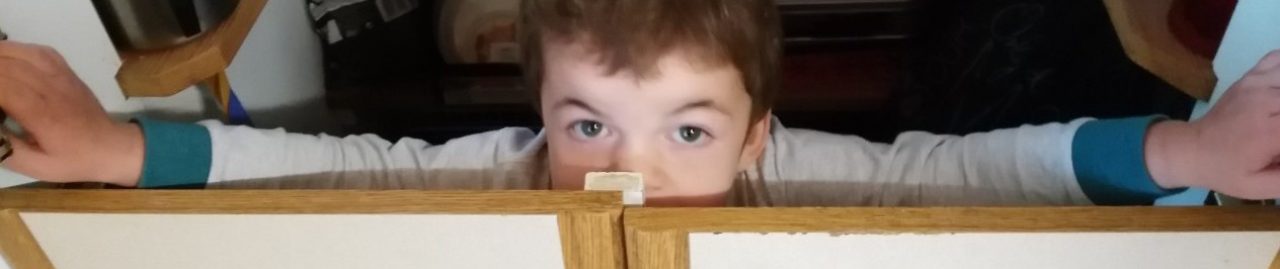

And then there’s Pudding…

When we got his diagnosis I was already struggling to deal with his whirlwind antics on a day to day basis. And now came the punch punch punch that MPS brings. Heart problems, general anesthetics, weekly trips to Manchester for enzyme treatments, issues with airways, joints…. Through all this there was the knowledge that he might be one of the unlucky ones, one of the ones with progressive Hunter Syndrome who will lose all his hard-won skills and die in his teenage years. That was confirmed in October 2015.

Then we were onto the next roller coaster of a clinical trial – the shaky hopes as we were hauled to the top and plunging despair as the reality of his decline kicked in, the impossible decisions that we were forced into making.

Now, all the hope has gone. He no longer has any treatment, only symptom management. We know that the inevitable will come to pass. Short of a miracle happening we will continue to lose him bit by inexorable bit. Anyone looking in from the outside might expect our situation to be much bleaker than the times I have described above. But with the hope gone we’ve also lost the deep lows. With the loss of Pudding’s abilities we’ve also lost the challenging behaviour. We’ve not necessarily stepped off the roller-coaster – I know there will be further ups and downs ahead – but most days we coast along fairly happily. Back then, I saw the future as a constant bleak decline, but in reality progress is more step-like with a sudden change followed by months of stability where we can settle into peace. After many years of saying I need to learn from him, to live in the moment, I’m pretty much there. And we have many beautiful moments.

Of course, it’s not all sweetness and light. Even Pollyanna had her down days. Ironically, reading the posts that I’ve linked to above I’ve just been crying again, but they’re tears for the me that was writing then. The me who was having to deal with all that. There are days that I cry for the future – a conversation with a doctor at Martin House triggered a vision of saying our final goodbyes to my baby. And there are other days when I cry for the now – when Pudding is unhappy and I don’t know why and can’t fix it, no matter how much I want to. Those times will undoubtedly become more common as we get further on.

But until then I am happy. In the moment.

To me, it was so much more than that. It was a reminder of the day our fears came true. The day, a few months after diagnosis, that we finally got the results from his DNA test, confirming a complete gene deletion and therefore the worst possible outcomes from his condition.

To me, it was so much more than that. It was a reminder of the day our fears came true. The day, a few months after diagnosis, that we finally got the results from his DNA test, confirming a complete gene deletion and therefore the worst possible outcomes from his condition.